|

IIMA - International Improvised Music Archive To Front Page...

|

by Vinko Globokar

This article has been translated by Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen from the French original published in musique en jeu 1, 1970. It appears here with the kind permission from the author and from C. F. Peters Music Publishers, Frankfurt/M., Leipzig, London, New York. A German version appeared in Melos 2, 1971, without the music examples.

The interdependence between composer and performer has nowadays become one of the fundamental problems in our music. Owing to recent experiences and acquisitions in aleatoric and graphic music which among other things developed a responsibility from the side of the performer, it is a desire today to let the performer participate more deeply in the musical creation. We would like him to engage himself totally, not just use his technical proficiency about the work but also his capability of inventions, his ability for decisions and more or less spontaneous reactions, in one word - his "psychic contents". Nevertheless, we would like to preserve the possibility of being able to "conduct" - to canalise - the different forms of this participation.

We have already made an experiment: the more we are transferring the responsibility of composing to the performer, the more we run the risk of creating musical situations which will jeopardise our aesthetic view. This is why we are looking for some technical means which primarily stimulate the performer to an extremely engaged participation and which at the same time eliminate this most frequent fault: the use of personal clichés which he puts into play as soon as you appeal to his invention. On the other hand this technique must allow for a dynamic change (1) back and forth between those situations having a maximum of responsibility from the side of the performer and those in which the performer does nothing but reproducing a totally fixed/composed music.

It would be an aberration to prescribe to a musician: "At this point, improvise" without giving him previous orientation. The rare musicians for whom improvisation is a vital necessity have no need for this frustrating occasion (2). To them, this seems to signify: "At this point, you should undress". They do it when they feel the need to do it but definitely not when being ordered to. Those skilled musicians who are superficially initiated in this practise, find in this case an occasion to expose a repertoire more or less full of their own personal clichés. Most orchestral musicians will interpret the prescription his way: "At this point, do whatever". The two last attitudes are understandable, as in principle the compositional process takes place rather strictly within the aesthetic ideas of the individual composer. Because of a lack of sufficient indications, the performer participates in a subjective way. Being in most cases not initiated to the aesthetic and stylistic conceptions of the composer, he cannot figure out his silent wishes. Presented in this way, the musician's participation is clearly not constructive.

A different means to make the performer participate in the creation of a work became especially the object of experimentation in recent years. This consisted of inviting a choice between a limited number of different possibilities. For instance: choose freely among a group of prescribed notes, choose between given structures, choose one of several possible ways, etc. We have been able to establish that this lead in most cases to a demonstration of open disinterest in the offer given to him to participate in the construction. The act of choosing is above all an intellectual operation. Experience has showed us that the performer is especially interested in those operations which are more directly musical, more interested in tasks putting him directly into contact with the sounding material and thus excluding operations based on decision, choice or a reasoning which has been pushed too far.

If we give him the possibility to react on sounding contextual material, whether composed by us or selected by us, this will have strong chances to yield the desired results: 1) evoking deep interest from the musician, 2) having the possibility to "canalise" his imagination and invention in the service of the work. If you want a performer to react, it seems necessary to "send" him a stimulation of a visual or acoustical kind. What interests us is the quality of reactions provoked by stimulations from different sound sources.

Simplifying the matter, it is possible to qualitatively catalogise the reactions which we can prescribe into five categories, fundamentally different from one another.

The most direct and instinctive one is no doubt IMITATION. After a variable time lapse, the performer is to reproduce exactly what he heard. Clearly, the spontaneity as well as the quality of the response will depend on the contents and character of the model, on the degree of its complexity and on the degree of its perceived difficulty. Only very few performers have a sense of absolute pitch; thus we must take into account a certain groping for the result when dealing with exact imitation of given pitches. In the same way, the time lapse separating stimulus from response varies much according to every performer's "spiritual presence". Imitation is a spontaneous reaction, it happens almost instinctively, with neither much reflection nor conscious analysis.

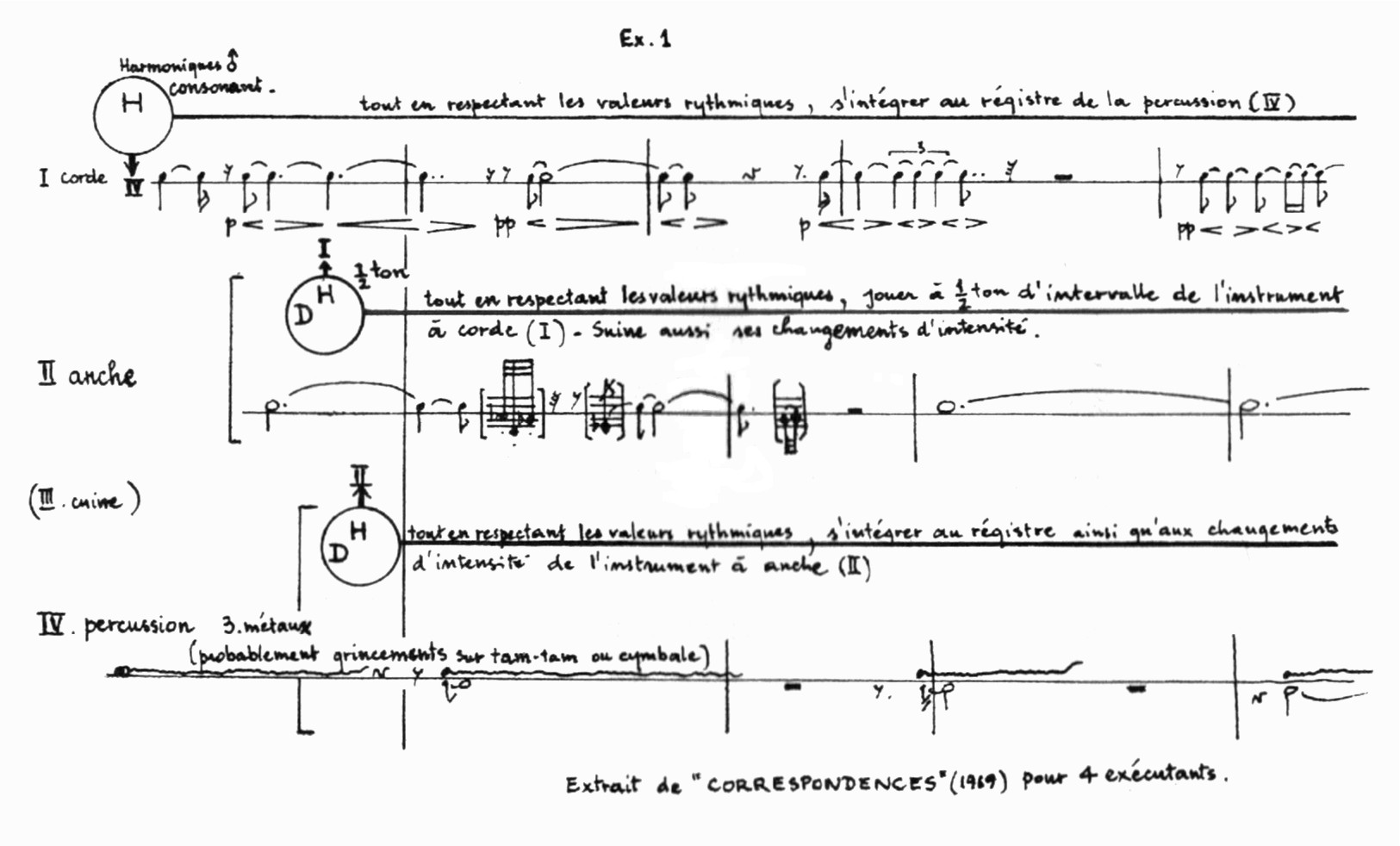

Instead of imitating literally, it is possible to INTEGRATE ONESELF into a material serving as a model, to follow it, to incorporate oneself into it, to move into the same direction. In this case, the response differs from the proposed material above all in the details. One perceives subtle deviations taking place alternatively in all parameters. The sounding results coming from this group of reactions reveal aspects of embellishment, of disguising or reinforcing, and certain intentional deviations from the established road may entail short developments of fragments having been discovered within the model. For the performer, this group of reactions remain rather manageable. The performer can always find a possibility of integrating himself into the model in one way or the other, and so the degree of complexity of information does not play a decisive role. (Ex.1)

To HESITATE, with further variants of paying no interest or making only sporadic interventions constitutes the group of tasks tending the most to creating distant and disengaged attitudes. Starting from being "tied" to a certain material, the performer arrives at creating active halts, extremely alive and tense rests by means of these prescribed reactions. He takes bits out from the model and places them in time, transformed and in a subjective way. Hesitating may produce an inner tension in the performer which a totally fixed writing would probably have been incapable of provoking. Idleness in music, which in rather many cases makes for a dead situation, becomes here extremely "constructive".

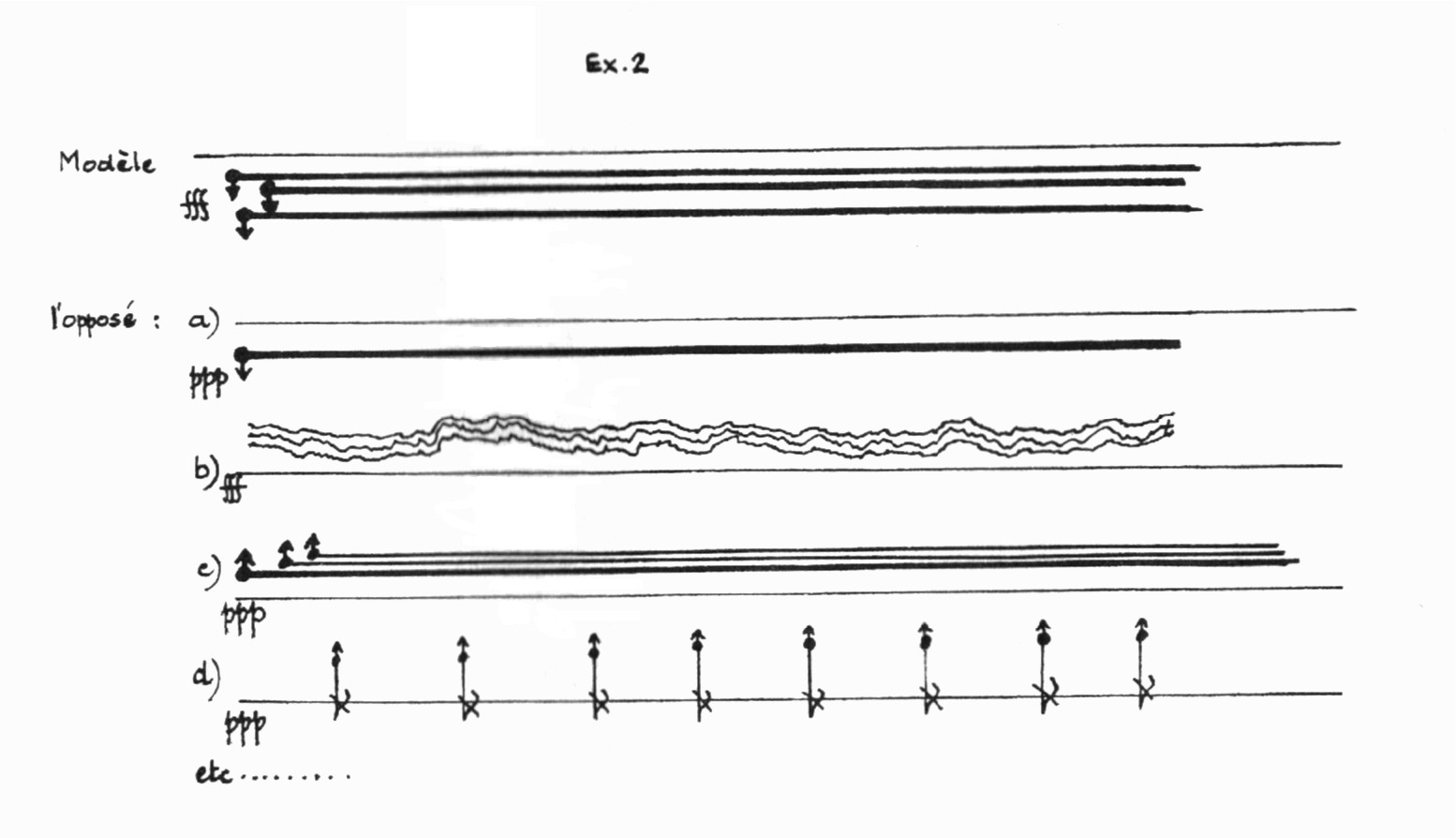

There is a fundamental difference between these three modes of reaction (imitate, integrate oneself and hesitate) and the reaction consisting of DOING THE OPPOSITE. In the previous cases, the performer did not reflect nor analyse consciously. He employs his musical sense, instinctively and in a fair number of cases even intuitively. Contrary to this, from the very moment one demands him to react to a model, doing the opposite, he has to rapidly analyse the situation, dissect it into parameters in order to become able to subsequently decide what could be the opposite of the heard situation. Following experience, one has been able to establish that everybody "chooses" the parameter or parameters appearing to him to be the most characteristic. Ultimately, he does not "choose" but reacts. One type of material, proposed with maximum loudness, static, in a deep register, will be "opposed" according to the individuals in one, two or even all three parameters at the same time, whether it be ppp but remaining static and deep, moving and high but remaining fff, or ppp and high but remaining static, etc. (Ex.2).

The selection of one or several parameters which seem important followed by the creation, the invention of the opposite of them is a reactive but in the next place compositional process. (3). The spontaneity of reaction which we have been able to establish in the precedent cases was tied to a certain qualitative uniformity, because the performers would have rather similar and predictable responses. In the case of doing the opposite and even more in the fifth case - DOING SOMETHING DIFFERENT - this instinctive but uniform spontaneity gives way to a multitude of possible responses, in which every individual has an interpretation of what to do with the prescription, together with an entirely personal perception and analysis of the model. We might say that he rather "composes" his response in the case of doing the opposite and that he invents his response in case of doing something different. Especially in the last case, there may appear risks of moments coming up which do not any more correspond to our aesthetic views, but they are rather suppressed by the fact that the performer is conditioned by the contextual material and can only with difficulty escape the stylistic context of the model.

It is especially in these two last cases that the personality of the performer at last has the possibility of emerging and that his musical culture, his "reservoir of possibilities" plays a decisive role. This poses the question whether we are writing the music for a group of performers with whom we work regularly and with whom we live on a basis of deep friendship, or whether we are immediately composing our music for unknown performers. In the first case we know each other mutually; this means that the performer knows more or less the aesthetic points of view of the composer, and he knows more or less the depth of the musician's "reservoir of possibilities". Thanks to this knowledge and this collaboration, also thanks to the possibility of experimenting and discussing points of misunderstanding, the prescription of reactions like "do something different" or even proposing something new, without anything musical supplementing it, becomes possible and extremely fruitful.

Not having the possibility of working in a group and writing directly for unknown performers, without having the possibility of talking to the performers, one has to be conscious of the fact that verbal prescriptions like "do something different" may yield unpredictable results, arising completely out of our conception and our desires. In this case one must be honest and, without contenting oneself with hoping for the best (4), we must know whether we wish for the responses to be exclusively within the order of that which we could foresee, or whether, on the contrary, we accept also the impredictable, not only the strictly musically impredictable but also the aesthetically impredictable. The more we want to control the result, the more it is consequently necessary to tie the performer to precise conditions, prescribe reactions with predictable results, to provide him stimulations of sounding material which is simple to perceive and to analyse, or to give supplementary indications in case reactions could lead to ambiguous results. Coming back to works addressed to the performers of a group in which we are working, in which we can allow ourselves to propose "tasks" to the performers which are susceptible of leading to unexpected responses (5), it is clear that even these works are intended for unknown performers. The advantage is that these performers, when asked to play the piece, probably will have a recording or a release at their disposal by the group to inform themselves by.

Until now we have been talking about results being more or less predictable, provoked by the prescription of five categories of reactions, omitting to mention the fundamental importance of, first, the quality of the information to which the performer is to react, and second, the origin of this information - the means of its dissemination.

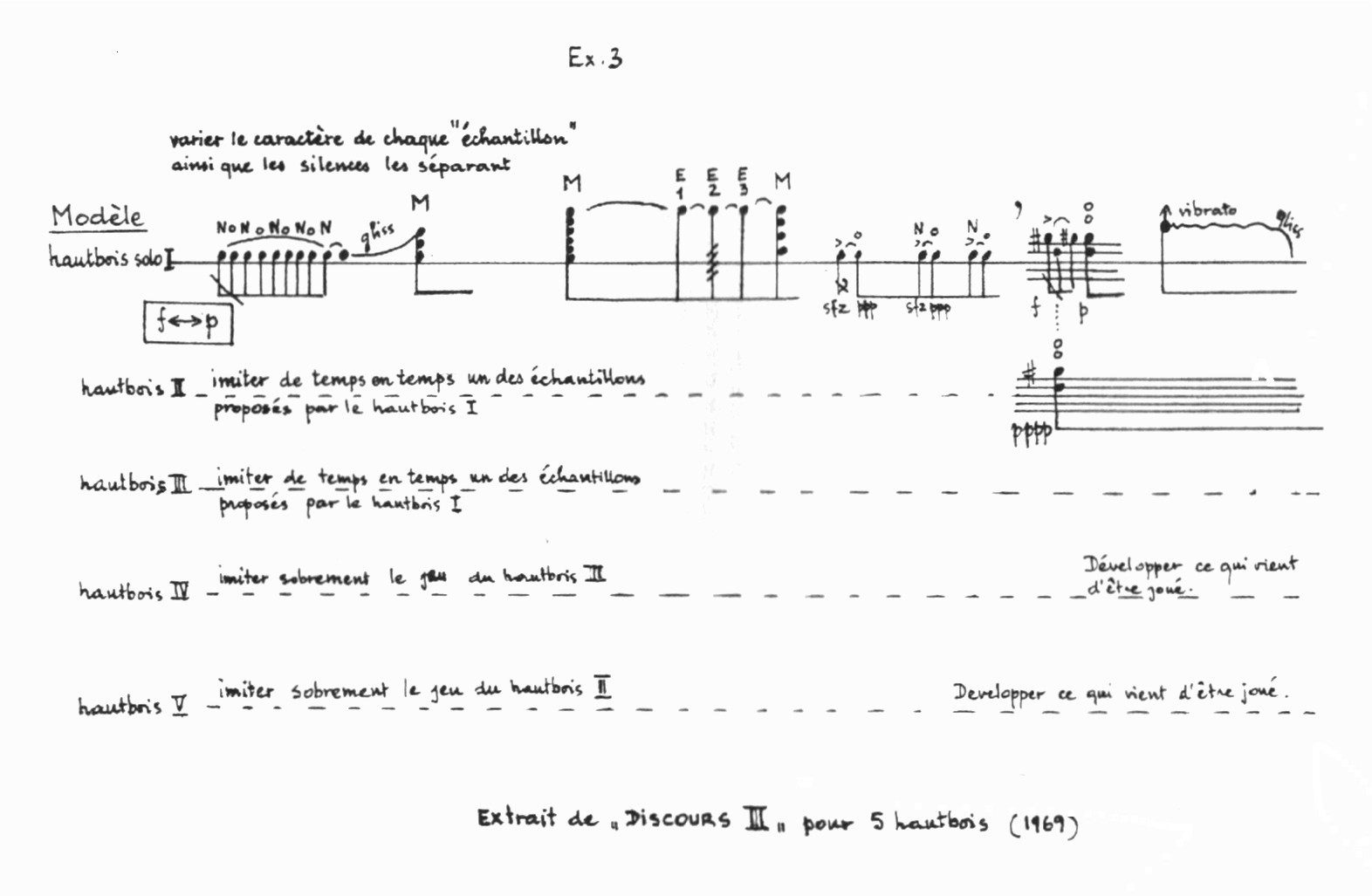

Clearly, we can compose a model which the performer is called upon to react to. This is, however, not a very interesting solution, since the performer, after several rehearsals, will know the material, and the spontaneity disappears. In principle, the information given out should be constantly different, in order that the performer cannot predict the nature of it and is forced to stay attentive. This is because it is necessary to include a portion of chance if we wish to compose the information; it must contain the possibility to present itself every time under a new aspect (Ex.3). These composed informations are nevertheless simple; being composed, they are in principle "musical". On the other hand, letting an instrumentalist react to electronic or concrete noises, or going beyond all reservations to let him react to the human language or even that of an animal, to a yet unknown acoustic world, in one word, all that which is "extra-musical", can yield results the sounds of which we are not yet capable of foreseeing.

The instrumentalist, obliged to approach with his instrument a sounding model, being till now completely unfamiliar with its possibilities, finds through the force of the stimulation, maybe rationally, but even more often instinctively, new solutions, thus enlarging also the present personal limitations.

Concerning the dissemination of acoustic materials, one can imagine the greatest variety of sources - tapes, discs, radio, all this distributed by loudspeakers or headphones. Almost unexplored are moreover the various aspects offered by the reaction between performers. Even the relation: performer-performer - in which, for example, a performer, having material at his disposal which we have prescribed him in an incomplete form "searches for" the absent elements (which are, however, necessary if he wants to play) within the playing of his neighbour - yields extremely tense and engaged results. Even more interesting are the situations which oblige the performer to react simultaneously to the playing of two of his neighbours, thus having to analyse two materials at the same time.

It seems important today for us to create relations between performers in order that they should be tied more closely together, that they should be interdependent, that they should have the possibility of influencing each other. Exactly if we succeed in creating a variety of relations between them, not just musical ones but also psychologically, we arrive at making them interested in participating.

There is a common wish to "humanise" music in these days. To arrive at this, we must take a risk and first "humanise" the tasks of the performers.

Writing out each and every dot over the i letters when composing is a highly creative historical process, in which we (the composers) are responsible for everything. This process, whatever one might say about it, does not seem to satisfy us any more, because we wish for a "compositional" collaboration from the performer's side.

Trying to make the performer participate through abstract tasks, often being extremely complicated, formulated through a number of visual symbols, does not seem to be an ideal solution. The method is probably too rational.

Going to the opposite extreme and letting the performers improvise will not bring really constructive results. In most cases a chaos results, but even more often an eruption of the most superficial emotions of the performer. Clearly, that does not prove the non-existence of performers capable of creating music full of qualities and possibilities opening towards the future on a basis of quasi total freedom. They probably announce a new era, but do not solve the problems we are preoccupied with.

One more reflection of a chiefly moral nature: it is evident that the more the performer is engaged "compositionally" in the creation of a work, the more this works becomes a product of collaboration, belonging as well to the performer as to us. This work is not just our work any more, it becomes the work of all those who participate.

=====

Notes:

(1) I am thinking of a transition which does not upset the performer.

(2) These musicians have nearly always the impression that you steal something from them which is their own. And what is more, in such cases it is impossible for them to unfold, to go where their intuition leads them, because they have been conditioned by what they have previously heard. This is why I make the summarisation "frustrating".

(3) Every performer, from listening, selects what he finds to be most perceptive (most logical, most interesting). And so, after having selected and analysed, he invents the opposite of this selected material. This is why I say the process is in the first place reactive (selection), in the next place compositional (invention of the opposite).

(4) Often, the composer presents aesthetic difficulties - but he counts on the presence of competent performers who can understand it and find a good solution. This is the "hopefulness", which in most cases will be disappointed, I am talking about.

(5) I mean: giving practical tasks.

====