|

IIMA - International Improvised Music Archive To Front Page...

|

|

This article appears in a simple HTML-version: there's just a limited amount of hypertext. To see the footnotes, you must go to the end of the document. All the text is on ONE page - therefore, you can copy or download everything from here, but please be aware of the illustrations! You can navigate with the 'back' and 'forward'-buttoms, and you can also use your browser's standard search tools (on PC, for instance Ctr-B) to search the entire document for any text string. |

INTUITIVE MUSIC AND GRAPHIC NOTATION AT AALBORG UNIVERSITY. ON TWO MUSICAL TRAINING DISCIPLINES WITHIN MUSIC THERAPY EDUCATION AND THEIR THEORETICAL BACKGROUNDS (1999).

Size: 103 KB plus illustrations

![]()

by Carl Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Aalborg University, Denmark.

CONTENTS:

INTUITIVE MUSIK - ITS FUNCTION AND FRAMEWORKS

Improvisation training

Training in creating compositions for improvisation

INTUITIVE MUSIC - CLINICAL RELEVANCE

GRAPHIC NOTATION - ITS FUNCTION AND FRAMEWORKS

GRAPHIC NOTATION - CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Music history

Therapy theory and theory of science

Philosophical views of music aesthetics

The idea of an 'intuitive music'

Music notation and musical analysis

Parameter analysis

Bruscia and parameter concepts

THE NECESSITY OF MUSIC RELATED CONSIDERATIONS WITHIN MUSIC THERAPY

LANGUAGE THEORY AS A LINK BETWEEN PSYCHOLOGICAL AND MUSICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This article

- introduces the two subjects, primarily with the purpose of passing on experiences to colleagues involved in the training of music therapists, although the themes treated here may also have relevance in a music education context. Glimpses from the teaching and from work produced by students will be presented, and their clinical relevance will be described.

- describes the theoretical backgrounds of the two disciplines in the context of music culture and music studies. Furthermore, it discusses how we can arrive at a unified understanding of the way music and therapy work together in an interdisciplinary context to which both psychology and musicology contribute.

Thanks to Simon Procter for proof-reading.

INTUITIVE MUSIC - ITS FUNCTION AND FRAMEWORKS

The function of this discipline is to train students in free improvisation in groups and in creating open compositions on the basis of insights grounded in musical analysis of improvised music processes. It aims to give students the basic skills they require as improvising musicians and to support their future activities as independent music therapists.

Didactically seen, courses are training processes which are largely teacher-directed, but within which the process itself receives much consideration. It is important that participants learn through personal experience how attention to the sound and to the playing process can increase flexibility both for individual expressivity and for individual as well as collective imaginativeness. It is also important that they learn some concrete concepts which can be used for understanding and memorising these experiences. As far as time limits allow, our own work on the course is thrown into relief by listening to recordings of improvised concert music. In the examination, students demonstrate their skills as composers of pieces which allow room for improvisation.

The courses are organised as blocks of 10 lessons, each of which usually takes place on three consecutive days in the first, third and sixth semesters. The theoretical background for this discipline comprises among other things music history, philosophical music theory and modern/experimental composition.(1)

The training can be divided into two main areas:

1) improvisation training

2) training in creating compositions which allow room for improvisation.

Improvisation training

Strictly speaking, one cannot teach people how to improvise. However, one can certainly attempt to remove inhibitions and awkward approaches to instruments and playing, to show people that they can improvise on their own, and to give them tools to be used at their own discretion.

Essentially, our only "goals" in working with free improvisation are those of being together in sound and following the common process. My system of exercises, which has grown out of practice, comprises the following:

- basic exercises, good for starting

- group-dynamic exercises

- awareness exercises

- parameter exercises

This functions as a palette of possibilities, and I shift between them freely according to our needs. For the start of the first semester course at AAU, I normally use a variant of an exercise called "Instrument-Storm".

|

Instrument-Storm (recent version) ............................................ This exercise aims to encourage participants to explore a number of instruments and to introduce playing together. Participants are given instructions along the lines of "Explore at least x instruments, playing each y ways in z minutes" - for instance, at least three instruments, each to be explored in at least 2 entirely different ways during 10 minutes in all. This can be repeated after a discussion of what happened, with additional instructions added according to the needs of the group. Work according to the "x y z" formula may be preceded by or substituted with a free "excursion", perhaps within an agreed time limit. Again, this can be repeated as required. (...) This exercise can link into other exercises and into more free forms of improvisation where participants can put their newly acquired experience to use. |

It is important to take into account the target group, the particular people in question and their group process. With target groups other than university students - for instance, musicians who are specialists on one instrument or young people who need to let off energy, the starting procedure can be quite different!

Amongst AAU students, the decision to become a music therapist is of course highly motivating for their training work, but there can be considerable differences between participants as to how shy or daring they are during playing.

Exploring instruments is not just a means for getting started. It should also give a concrete idea about the manifold possibilities for expressing oneself and reacting, using the right tools at the right time - or, if necessary, inventing ways of playing which suit the situation. Written materials giving further ideas for extended playing techniques etc. are given to participants.

Free improvisation without rules can either run into deadlock, giving a less than satisfactory experience, or else it can unfold in a way which inspires participants. The teacher should facilitate the process, provoke, show possibilities and make them concrete in the form of new instructions. When the process moves, highly engaging discussions can arise - for instance on the theme of the possible functions of music between people. Our "normal" ideas about music and what constitutes it do not really cover a situation where one is successful within such a high degree of freedom!

After starting, a group-dynamic exercise is often useful. This category deals primarily with the individual's use of rests and silences. "Cutting Down on the Material" takes this as its theme by instructing each participant to restrict individual soundmaking to (for instance) 3 stretches of 2 seconds each within some minutes. This may feel totally absurd when the instruction is given, yet the playing process and listening to a recording afterwards usually shows that what was lost in freedom of elaborate expression becomes more than compensated for by the group's highly increased sensitivity and reactivity. A subsequent free improvisation may become radically different from previous ones after this experience.

Awareness exercises deal with motivations for playing: with emotion, feeling and fantasy as well as with listening. Since music therapy students have many opportunities to work in such areas, I use these exercises only sparingly at AAU. However, "Listening to surroundings" can be useful: participants listen without interruption to the background sounds of the environment where we are. Just one minute of listening can give an experience of an opening up of the sense of hearing. Previously unnoticed sounds usually come to the forefront of one's attention.

Parameter exercises form an important category which also sharpens attention but centres around the concrete sound. Each sound has many dimensions: volume, pitch, duration - and in a complex sound pattern one could also consider the density of the overall sound (between the two extremes of everybody playing and everybody being silent). Even if traditional concepts of harmony and melody are abandoned in freely improvised music, the resulting sound can still be described - a comparable practice perhaps to that of chromatology amongst visual artists. The improvisation is not just "something" of amorphous character. Its specific shape, regardless of complexity, can be perceived and described using concepts, with the effect that

- one can more easily remember what happened

- during playing, the music can feel less chaotic

- one can respond quickly to the situation during playing

- one can discern which possibilities have not been tried and in this way relate more consciously to musical habits.

This suggests that our intellectual capacities can work very well together with fantasy, feeling and emotions in a process which is at the same time reflective and characterised by feeling - a powerful combination! "I didn't just experience this as some kind of trip, but found I was concentrating within it too", a student remarked. Fantasy becomes more powerful when combined with the musician's experience. I have a favourite saying which I apply both to working with instruments and to working with parameters of sound: "The musician is the most important instrument". A good musician can do a great deal even with very primitive instruments, and both practical skill and fantasy are decisive in this. Parameter concepts serve to support the fantasy by making it easier to perceive that which is sounding. "I discovered I could talk concretely about music which I otherwise view as rather unconcrete", a student remarked.

Until recently, parameter exercises were practised in a culminating exercise called "The big parameter exercise", in which more and more parameters at a time were varied freely. This exercise aimed to enable participants to discern that which lies, so to speak, "in the blackness between the stars". In other words, to expand awareness of the infinite possibilities for movement in sound - for its collective moving. Once, after a lesson in which we played five times for one minute and listened to recordings, a student remarked that "a lot has happened in music during this lesson". Quantity is not everything!

The new five-year curriculum, introduced in 1996, added an extra course in the third semester, thus making it possible to train participants in single parameters and to repeat exercises over subsequent days. This plays an important role in the third semester (in which students are not required to write compositions), promoting more precise learning of the concepts and making it possible to address more closely the specific needs of the group in question. Individual parameters each have their special mode of operation. The intensity connected to increasing density - more and more parts "hurrying towards activity" - is different from the "insisting" quality which comes from music becoming louder. A timbre shimmering into increasingly light shades (i.e. with more and more high overtones) might "creep up" on the listener. Increasing durations could give an impression of "mightiness and seriousness". And so on.

It is significant that humorous episodes occur not infrequently in the music. Maybe the playing of intuitive music outside therapy yields particular possibilities of playing with musical expression, since no fixed theme is being worked on - even though the explorative process in music therapy can also be playful in character. Something which can particularly invite humour is stylistic clashes (which can be studied consciously as a parameter exercise): the solution to the problem of "the others playing wrongly" (although, as we know, nothing can be called wrong in free improvisation) can be found in a humorous insight! "It is cool: it can also be fun" and "I have never before experienced dying with laughter whilst playing" are examples of students' comments.

The fact that we work with exercises posing specific demands should not be misunderstood. There is no teaching of models of how the improvisation should happen. The intention is to widen the horizon of possibilities so that no obstacles, be they of a technical nature or due to lack of fantasy, impede participants' ability to follow developments in the musical moment when playing freely.

...

In the last course in the sixth semester I usually present a "Playing rule exercise", the aim of which is to connect our experiences of describing the sound with the music-therapeutic practice of formulating a playing rule. A music example is played, and participants are asked to formulate possible new playing rules for an imagined improvisation which could follow and which might release some unexplored possibilities. These playing rules are to function as concrete titles for the music itself or as concrete musical roles (like "firm pulse" or "as long tones as possible" etc.). Thus, they will relate indirectly (suggesting or exploring via a projective procedure) to definite psychological content.

One further activity to be cultivated to the extent which time allows is listening to recordings of concert performances of improvised music and discussing them. This offers new experiences, contrasts with our own way of playing and nourishes reflection.

Further exercises have been described in Bergstrøm-Nielsen (1990ffA) and the English edition of the same booklet Bergstrøm-Nielsen (1990ffB).

Training in creating compositions for improvisation

This discipline can be viewed both as a special training in describing and directing sound processes (through the formulation of playing rules) which strengthens music therapists as they prepare for the task of conducting therapy - and as a discipline which in itself could be useful in contexts of a more pedagogical nature. An additional aspect could be that the student experiences herself or himself in the role of composer and learns to prepare and present the activity for others who listen.

The form of training is simple: during the first course various examples are presented to participants, and some of these are tried out in practice. After being instructed that the compositions must specify musical parameters and provide for changes in the process during the piece, participants create compositions as homework over the following days. Compositions are to be easily realised and to be of short durations, five minutes or less. All compositions are played and discussed. A similar task is undertaken, again by each student in turn, during the sixth semester shortly before the examination.

There now follow two examples of compositions created for the examination by students. They show how parameter concepts can be used for creating musical structures. They are played without conducting by a larger group whose members co-ordinate themselves loosely in relation to each other. This is what I have named the "picnic principle". The more subtly and ingeniously one can work out this principle, for instance by using cues etc., the better!

Figure 1.

|

"Sprout" |

"In flower" |

"Withered" |

|

little, short sounds |

Free improvisation |

long sounds |

|

staccato - accelerando |

Espressivo |

Morendo/slowly declining |

"Sprout" - "In flower" - "Withered" by Sine Baggesen focuses on the duration of sounds. Employing a simple and effective contrast of extremes in this parameter, a story about the life of the plant is structured. It seems to be characteristic of the medium of music compared to verbal stories that the music will function well with a limited number of clear phases and that a wealth of details in a story can be difficult to cope with in music. Consequently, students are recommended to aim at a certain formula-like and stylised character, as has been done here. Even if the long sounds are effective for the illustrative purpose here, they are of course, like the elements of music generally, not semantically unambiguous. For instance, in another composition by Ingrid Irgens-Møller long tones have been used to depict the majestic and calm character of a sea, into which flow smaller streams.

A certain norm has formed itself little by little: the composition has titles, drawings and specifications divided into approximately three sections. The different modes of expression appear to support each other in a convenient way.

Figure 2.

|

HOPELESSNESS |

DEATH |

|

TRANSFORMATION |

|

- atonal |

- single tones/chords are played for a duration of 4 pulse beats, then pause during 4 pulse beats |

|

|

|

- high or deep tones |

|

PAUSE |

Group divides into two sub-groups - they come together in a dance: |

|

-harsh & shrill timbre |

- timbre is dark and soft |

|

- tonal playing, light timbre - atonal playing, dark timbre |

|

- fast pulse pulse becomes slower and finally stops |

- finds a new common pulse |

||

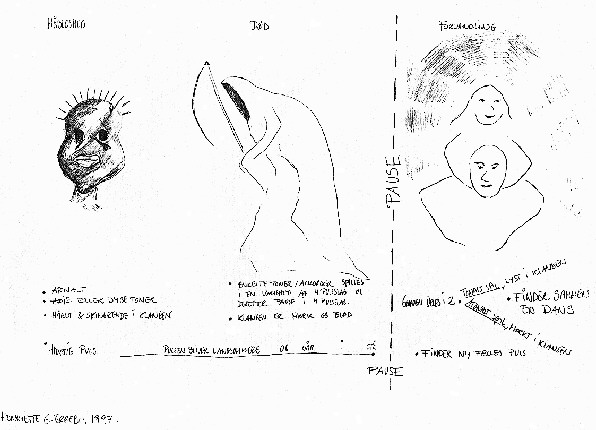

"Hopelessness" - "Death" - "Transformation" by Henriette G. Errebo shows more parameters in use:

- high/deep tones

- timbres (many different)

- fast/slow tempo

- tonal/atonal

- pulse/no pulse

Change of tempo in traditional Western music is a rare phenomenon. It is used here as a dramatic agent. Tonal/atonal as well as pulse/no pulse are parameters of particularly strategic importance for the integration of traditional music forms with those more generally dependent on sound, and they have been used in an original way. These dimensions, which so often constitute firm frameworks for music, change gradually here, again with a dramatic impact. It is important to understand and experience that opposites need not have a fixed relation to each other, but that they can "dance" together. Within the process, the pause is a sophisticated detail. It not only ensures co-ordination in the group's resumption of playing, it is also liable to lead to a hesitant and cautious new beginning. This is wonderfully concordant with the story the piece is telling us, where this pause marks out that which is totally unknown.

As is so often the case, in these two works I perceive an innovative and effective use of an expanded universe of musical sound.

INTUITIVE MUSIC - CLINICAL RELEVANCE

It is possible to become accustomed to free improvisation simply by taking part directly in therapy, individually and in groups. But "therapy free" improvisation training (an expression coined by a student) offers opportunities to learn short cuts, and gives a musician's feeling of independence which can be useful or even decisive for working alone in the long term.

Being able to imagine the music with one's inner ear, to possess notions which can grasp sounds, structures and processes while at the same time being able to use a varied selection of instruments and the voice in an agile way - together these constitute the musician's competence that appears in the clinical situation as alertness, initiative and authenticity. "It's good to make intuitive music after therapy - it helps me to discover how I use my sound" - "This is highly client-oriented - it deals with going into their tone" - "It has been good to get more direct contact with musical expression" - these statements from students suggest how the musician is an important part of the therapist.

Viewing the compositions dealt with above from a psychological perspective, we can observe that the composer here takes participants (and listeners) to definite places and through a definite process. Leading and suggesting is in the foreground, whereas the therapist's work is often characterised by a patient and relatively indeterminate exploration in which the essentials gradually appear more and more clearly. In many cases, however, what is experienced clearly is also clearly formulated, and in these moments musical and psychological qualities in therapy music can merge into a synthesis. The music therapist will in some cases need to influence the process in order to encourage it and to keep a balance within existing time limits, and here it can be essential to be able to think in musical structures - cf. comments above about the "Playing rule exercise".

This ability can also be useful even if playing rules are not formulated verbally. "I found that the ability to make music out of nothing was useful in real life", a student once commented.

|

With one of my first clients, an autistic girl, I needed to develop ways of accompanying her which did not dominate her quiet humming. At the same time, I felt that this accompaniment should not be a passive one, but one that could also stimulate and provoke her out of the monotony which gave her so little room for personal expression. My solution to this involved changing tempos, changing sounds and a varied use of pauses - all within a quiet piano range which could nevertheless contain short exceptions. Often, when making music with her and when preparing and analysing the sessions, I felt that my previous experience and interest in improvised music was helpful to me. It led me to see this long, patient work in the accompanying role as a musical challenge. I saw the accompaniment for me as a polyphonic structure (as in Stockhausen's "plus-minus" notation) and could motivate myself to go on patiently, seeing it as a challenge to invent new and relevant ways of accompanying. |

As improvising therapists, we need to be flexible and able to react to the needs of many different clients in a variety of ways. Also, we will need to develop ourselves as improvising musicians to keep our energies fresh over many hours' work each week and over the years.

Finally, it should be mentioned that skills in applying analytical concepts to therapy music are of course also useful to those who do research and to those who speak or write about music therapy in lectures and articles.

GRAPHIC NOTATION - ITS FUNCTION AND FRAMEWORKS

This discipline serves to train students in describing music improvisations using suitable symbols and drawings. Notations may range in size from short sketches to long analytical representations. In this way, details of therapy music can be grasped, remembered and analysed further. Thus the discipline aids the music therapist's description of and reflections on the particular work he or she is doing.

Didactically seen, courses are training processes which are largely teacher-directed, but adapted to the needs of the particular group. Individual participants develop their own language of symbols and visual elements. During the course they will work with various samples of improvised music and exercises gradually leading to elaborate notations.

In the written examination, students are required to create an elaborate notation on their own.

Courses take place as blocks of 12 lessons in the second and fifth semesters.

The theoretical background for this discipline comprises among other things modern and experimental composition with its new forms of notation and its offshoots into aural scores, as well as musical analysis. Furthermore, psychodynamic therapy theory is relevant, especially the three-zone model from Gestalt therapy.

Exercises here can be grouped into:

- preparatory exercises

- "stenographic notations"

- special exercises

- making elaborate notations

- exercise with 3 columns

Preparatory exercises comprise automatic drawing and sign-brainstorm. Automatic drawing is a movement improvisation on paper with a pencil or the like with closed eyes, and it may or may not have a theme. For example, the reader is invited to determine whether the theme of fig. 3 was "agitation" or "delight".(2)

Figure 3.

This exercise has always shown that clearly differing emotions (such as "agitation" and "delight") are depicted so that the viewer will perceive the difference. Any line drawn by hand expresses itself by means of its elementary, archetypical qualities. This is one reason why graphic notation can convey someone else's perception of the music without employing standardised symbols.

Sign-brainstorm is a brainstorm of all kinds of visual symbols - a writing down of what comes to mind of pictograms, symbols from maps, etc. etc. The reader is encouraged to imagine his or her own list of sign samples!

Continuing the exercise of automatic drawing can lead to "stenographic notations". The instruction for this runs along these lines: "Draw a line and let it move as it likes while listening to the music". Figure 4 shows a result of this.

Figure 4.

This notation, of an excerpt of one minute and 25 seconds of a saxophone solo by Lauri Nykopp is simple and sketch-like, but already hints at what an elaborate notation should be like - using "doodling figures" corresponding to specific sounds as well as sections shifting along with sections perceived within the music.

The work with "stenographic notations" continues through both courses, with increasingly difficult examples. More and more memorisation is required by notating only after listening, sometimes a long time after - a situation similar to that often encountered in real life.

An elaborate notation is created by consciously working out the notation and extending it in various dimensions - as focused upon in the special exercises. Some of these deal with inventing simple symbols for certain sounds that can be repeated, perhaps even in varied forms - an extension of the sign-brainstorm. Some deal with analysing and simplifying complex processes by dividing them into a limited number of sections and characterising them. Some require precise plotting relative to a horizontal time axis and a vertical axis which normally deals with pitch (but not necessarily).

Intensive work on the exercises and discussion of the results alternate with more free study of various notations by composers and other relevant material on paper or video.

Elaborate notations are characterised by their inclusion of a key to symbols and a time axis, and also by their aiming at a reasonable coverage of both the musical process in its totality and a certain amount of detail. They will often relate to a standard model, having approximately 3 sections, each with titles.

In figure 5 by Charlotte Lindvang, the notation immediately conveys an impression of alternating "heavy" and "light" sections and a culmination towards the end. The key to symbols demonstrates a good division of musical elements based on an analysis of the music example in question. This notation was created in the 1995 examination and covers, as usual, a time-space of three minutes.

The titles are: "Moving over the inner darkness" - "Longing, in the light" - "The strength (and courage) to meet anew".

Figure 5a.

Figure 5b.

|

Translation of the key to symbols: PIANO - LILAC THROUGHOUT. XYLOPHONE - YELLOW/ORANGE THROUGHOUT. ... : melodic and rhythmic movements resonating ... : deep, resonant tones ... : tapping the wood of the piano (the lid) ... : small rhythmic phrase with just two tones (or even just one) ... : arpeggio ... : "detached" tones (not melody and not arpeggio) ... : arpeggio ... : fast passage going up (xylophone sliding upwards) |

Figure 6 by Charlotte Dammeyer shows another notation of the same music.

The titles are: "On deep water. Do not know whether this is something for me. A little gloomy. Help" - "But I am curious. Would like to escape, but I listen..." - "Do not want to be "caught" - piano is chasing me" - "Contact. Now we are playing. It is nice."

Figure 6a.

Figure 6b.

|

Translation of the key to symbols: (first column downwards, then second column downwards etc.) metallophone piano, treble piano, bass hitting on wood or the like |

|

metallophone piano |

|

metallophone and glissando piano treble and bass |

|

metallophone piano |

In these two examples, symbols have been given different shapes according to individual criteria. For instance, the beginning of the metallophone is depicted in the first example by a line with stylised "doodling figures", but in the second example by separate symbols. Whereas the drawn line in the first example has a certain spontaneous, expressive character whilst at the same time being stylised, we have in the second example a simple, repeatable symbol for single tones. (Of course, this symbol is not totally schematic - by its vertical wavy lines it shows in an evocative manner that the tones resonate.) In the first notation, the depiction of the metallophone by means of a line is carried through the whole notation with one exception (the "lightning figures" towards the end), whereas in the second a new symbol is introduced for each section.

The two notations also have similarities. In both, the same general movement in registers can be followed: metallophone and piano making a common movement into a high register, the piano going down and up again, and an ending in which there is a dialogue in a high register. In both, a group of glissandi figures towards the end is marked out.

If one listens to the recording while reading the notations it becomes apparent that they give outlines, not all the details. But this is appropriate, since they were not created to play from.

The interpretative statements in the titles and design of the notation makes things clearer to the reader. When the process is described as an ongoing story, many details are integrated into wholes and can be overviewed and related to one another. In other words, entities are formulated on a semantic level.(3)

When compared on the basis of the titles, these two interpretations are seen to agree in describing something gloomy and heavy at the beginning and close contact between the two players at the end. But when it comes to the glissando figures near the end, they differ. The first interpreter sees them as an expression of strength and courage, whereas the second sees them as expressing active resistance against being caught by the therapist.

Despite the differences, both interpretations can qualify as introductions to a discussion with the client or about the client. The stories are fictive, intended not as diagnosis but rather as something to be creatively discussed. Implicit in the statements are "I imagine that...". The basis of such interpretations can be grounded by ensuring that the interpretation relates to the details of the music and is subjected to critical self-reflection. In this way, it is possible to approach a more exact description in psychodynamic terms of what is being worked with - still as an assumption. In this example one could guess at "a shy person works at having close contact with the therapist". Or, "the client works, with support from the therapist, at getting into contact with something sensitive inside himself or herself". The latter interpretation is the closer to reality. By contemplating the difference, it may become apparent that for the interpreter it can be hard to tell whether the personality appearing in the music is the normal and usual one or whether in this part of the therapy the client is, on the contrary, working with other sides of the personality.

The interpretative aspect is especially trained in the "exercise with 3 columns" which gives a point of contact with therapy theory. In this exercise, the music is interpreted on more levels using analytical concepts from gestalt therapy dealing with sensing, imagining and emotion.

The gestalt therapy three-zone-model makes it possible to formulate a critically reflected, personal conception of the content of the music as a basis for a psychological description which relates descriptively to the music as well.

Experienced reality is divided into zones: outer zone, intermediary zone and inner zone. The outer zone contains our sensing of the world around us. The intermediary zone contains imaginations - both fantasies and thoughts belong to this. The inner zone contains emotions and body sensations. Direct contact to reality always takes place through the outer zone (the outer reality) and the inner zone (inner reality). And it always happens in the now that is changing all the time. By contrast, the imaginations, thoughts and fantasies of the intermediary zone are "models of reality inside our heads". A common one-sidedness with many people is to use the intellect and the intermediary zone too much and the other ones too little.

The exercise aims at giving an insight into how we describe music on the basis of our personal resources of empathy, and it has the specific aim of showing precisely how our formulation of seemingly purely objective concepts can have as its background the therapist's subjective bias. This bias can result in the therapist projecting his or her individual concept of music and expectations associated with this onto the client - whose concept of music, in turn, might well be quite different.(4)

Students draw 3 columns on a piece of paper and describe the musical process so that each column has a reasonably differentiated coverage. Under "outer zone", they are to describe the music with words as concretely and descriptively as possible (for instance, 'flute plays short tones in high register'); "intermediary zone" is the place to enter imaginations and fantasies ('bird is hopping around timidly'); and "inner zone" is for the indication of personal states and emotions in the listener ('I get a slightly uneasy feeling').

Writing in all three columns ensures that we are in contact both with the music in question and with ourselves. Both single columns and the relationships between them may be investigated in many ways. For instance, the descriptions of the intermediary zone can be compared to those of the inner zone in order to see where the depth in the personal experience really lies. The description of the intermediary zone can be examined as a possible basis for graphic depiction - how many sections are there, and what are the differences between them? The description of the outer zone can be examined with a view to finding appropriate graphic descriptions of the sound, which symbols to apply etc.

The subjective bias can be scrutinised by first formulating one's own general concepts about music ('my definition of music') and after that critically comparing it with one's own concrete descriptions of the outer zone. How are my descriptive concepts characteristic of the way I perceive music? Acquiring a feeling for this can yield an enhanced consciousness of one's own limitations as an interpreter and thus greater realism in interpretations.

There are more comments on the gestalt therapy model in the section on theoretical backgrounds.

A closer description of exercises and method can be found in Bergstrøm-Nielsen (1992ffA and 192ffB). See also Bergstrøm-Nielsen (1993).

GRAPHIC NOTATION - CLINICAL RELEVANCE

"Stenographic notations" can help the therapist to remember more details for longer. This can be especially relevant when something important demands special attention or if a recording is an old one. It may also serve as an aid in remembering what happened in a previous session. And where there is no time for lengthy reviews of cassettes or videos, it may enable one to take a "short cut".

If one or more sessions are to be studied in depth, one can create an elaborate notation. This forces the therapist to make up his or her mind as to how the music is perceived, to go into details and perhaps to throw new light on them. Whilst a recording is bound to real time, the eye can make overviews of a picture in its own tempo. This can enable new structural relations to stand out, thus helping the therapist to "look beyond" their subjective bias.

Both small-scale and large-scale notations can be useful for communicating about the work of the music therapist, be it in supervision, treatment meetings, or lectures and writings. Pictures attract attention and can quickly convey an impression of relationships within a whole.

Finally, a regard for visual aspects can stimulate experiments in the creative use of visual art in music therapy - for example, drawing an improvisation afterwards, improvising on the basis of a picture etc.

Music history

Recent music therapy takes as its immediate background contemporary events in concert music. Music therapy utilised the new means then becoming to a certain degree accepted, and took advantage of the general state of agitation and the propensity for creation of the new which were current at the time when it established itself. Literature on music therapy which is both active and based on free improvisation begins to emerge in the early seventies. At the same time, some musicians from classical backgrounds began to form improvisation groups. Earlier, in the sixties, jazz musicians had already started to explore free improvisation.(5)

Free improvisation, in the sense of improvisation without previous agreements, presupposes that participants accept a broad and indeterminate universe of sounds and musical elements. One could call this an avant-garde attitude. Relevant insights for music therapy based on free improvisation can be gathered from experiences in new and experimental music. Here, work has been going on in depth, pushing the limits of the medium of music ever further, to the benefit of expressive possibilities, communication and understanding of the nature of music.

The keywords of SOUND and PLURALISM seem to be able to circumscribe some basic properties common to the ocean of new musical phenomena. Composers like Stockhausen, Cage and many others have contributed to this new music and to its theoretical ideas.

A characteristic of new and experimental music is its interest in SOUND generally, which goes beyond selected tones, major/minor and modal systems, rhythmic and harmonic systems etc. Instruments are used in non-traditional ways, electronic music has emerged - one might fairly claim that a broader spectrum of human expression has been opened up, one which permits an expanded range of emotional and contemplative possibilities. Another characteristic is the PLURALISM OF STYLES which has been unfolding in concert music since the sixties , (preceded, of course, by collage phenomena in the music of composers like Charles Ives). This pluralism of styles seems to be a natural consequence of the expansion of the musical universe. When any sounds can be used, a musical work can not be bound to exist within a specific stylistic state of pure cultivation. It can wander between styles or the style can shift from work to work. And one can quote - just as in everyday language with its practice of quoting others, sometimes with an affectionate, ironic or playful relationship between what was quoted and the context. Here, the universe of musical language is so to speak extended by the square power. For while the activity of cultivating new sounds in music could take place within a given, well-defined part of the avant-garde universe, pluralism makes connections to all other music and can throw light on the relationship between the known and the unknown, tradition and alternatives.

New conceptions of music have manifested themselves not merely as styles, but also as new forms of performing practice (improvisation), notational practice, musical analysis and aesthetics. These fields offer direct backgrounds for contemporary, active music therapy which takes free improvisation as its basis and more specifically for the disciplines of intuitive music and graphic notation.

Therapy theory and theory of science

The "topological" model of Perls and gestalt therapy with its outer, intermediary and inner zones form a useful mini-map of aspects of psychology of personality, of depth psychology and of psychology of perception. It was formulated for practical use in therapy and connects directly to psychodynamic contexts. Its clear separations render it suitable for a philosophical theory of science-orientated clarification of the concepts of the subjective and the objective because it makes clear what depends on the individual and what can be called common laws. In therapy it is of particular importance to listen to oneself (outer and inner zone), even if the notion of a relatively objective reality which can be intersubjectively demonstrated cannot be abandoned - although the conception of reality may be revised as a result of therapeutic work. In scientific work, by contrast, while the researcher may listen to his or her intuition it is nevertheless essential that concepts are clarified and classified, an activity belonging to the intermediary zone.

The subjective and the objective appear here to be interdependent, since each may in turn be given priority. In intuitive music there is a certain stressing of the objective dimension in dealing with the musical material, its nature and possibilities. At least when compared to the conception of music as a reflection of individual emotions and notions, this amounts to a weighting of the objective dimension. In graphic notation, traditional musical analysis undergoes a change, so that categories dealing with music history and music forms are put into parentheses and the interpretation of a specific content of a human nature comes to the foreground. This is a shifting of focus to something oriented more towards the subjective dimension, but without letting go entirely of descriptive endeavours.

Philosophical views of music aesthetics

Music therapy derives its popularity and motivation from the idea that music is interesting and exciting. The purpose of aesthetics is to formulate coherent views of the ways in which music is interesting and exciting.

Here, a few significant views will be mentioned which have been, and still are, of importance.

The music aesthetics of John Cage stress the importance of hearing attention, of the now which is ever shifting and the unpredictability of music. There is a striving away from fixed constructions and towards a moving process: "there is ordinarily an essential difference between making a piece of music and hearing one. A composer knows his work as a woodsman knows a path he has traced and retraced, while a listener is confronted by the same work as one is in the woods by a plant he has never seen before... What has happened is that I have become a listener and the music has become something to hear".(6)

It is no exaggeration to say that the music philosophy of John Cage is amongst the strongest influences on music of this century. It is also possible to relate to it in a more or less sentimental way by seeing it as a general homage to the joys of music. However, recent music therapy based on active participation by clients has taken up the idea of music as a process in a concrete way.

Another example is the serial principle, as formulated by Karlheinz Stockhausen as a general "geography" for musical sounds and their behaviour in music, which makes it possible to conceive of a multi-dimensional space - with all degrees between extremely high and low pitches, loud and quiet, movable and static etc. - as a map giving a sense of order and orientation amidst the utterly unknown.(7)

This principle is connected with the development of new, descriptive concepts about the parameters of music (see above about parameter analysis) and was preceded by the development of many types of composition and of instrumental combinations which composers employed creatively on an increasingly individual basis in the romantic period and onwards.

The idea of an 'intuitive music'

The subject of training people in group improvisation and creating open compositions for improvising players has been called Intuitive Music since its inception.

This name was introduced in 1968 by Stockhausen, who applied it to two collections of his compositions, notated with text and published in 1968 and 1970.(8) Around the same time, the composer toured with a group playing the music of the first collection, and recordings were released. Stockhausen wrote articles about this, and in addition there is a useful published discussion.(9) Thanks to him, the name became relatively well-known in new music circles.

It has sometimes also been used by others. Various concert groups with names along the lines of 'Group for Intuitive Music' have existed in Denmark since 1974 and, related to these, a yearly international Intuitive Music Conference has been held since 1995. Additionally, in Denmark and elsewhere, the expression "intuitive music" can sometimes be heard denoting improvised new music in general. It seems to be significant that the expression can evoke associations of both individual freedom and of something meditative.

The propagation of the name is not, of course, a matter of scientific calculation. But one could, in accordance with Stockhausen's original thoughts, attempt to render the concept of "intuitive music" definable.

Stockhausen wished to stress that the music was seeking a way out of pre-defined cliches(10), and he defined intuitive music by contrasting it with improvisation within a style. For instance, a jazz musician may have a certain repertoire of figures, motifs, phrases etc. which are consciously repeated time and again. Thus, intuitive music means "intensified improvisation" or "radical improvisation". The fact that he introduced this as something to follow on from playing within composed frameworks or starting points may appear paradoxical. But in its context, it was a very radical step away from playing from notes both for Stockhausen himself and for the musicians.

The concept can be viewed as a Utopia which one can approach but never reach, as is the case with Stockhausen himself. An interesting half-way point between this view and a plain musical genre name would be to maintain that the ideal is reached at certain moments. Music therapist Anne Møller Jørgensen describes the concept like this in her final paper: "I view...intuitive music as a synthesis - a total realisation in a spontaneous expression...I would like to stress that I see intuitive music as a rare jewel within improvisation, but also that this itself can to a high degree be regarded as a moment of transition.".(11)

It is an interesting question whether intuitive music existed as a conscious and consequent endeavour before Western new music in the second half of the twentieth century. Stockhausen thinks it did not. But it is tempting to believe that somebody or even many people must have had the idea before. The idea of a free stream of consciousness seems to be of a similar nature, and this is described in ancient texts related to yoga meditation. But on the other hand, meditative music in many cultures is often a very fixed ritual - it is not within the medium itself that one lets go of thoughts and feelings. One relevant practice, however, is the "dream-chanting" of Charlie Morrow which he learned from studies with American Indians - a practice which could have its roots way back in time. Here, dreams which one feels are important are re-told by means of freely improvised song. But other than this, there is a striking lack of historical evidence.(12)

Music notation and musical analysis

Music notation in our culture went through many stages before the appearance of its most recent version in the sixteenth century. And when some of the new music in the twentieth century took an experimental direction, new kinds of notation were included. Completely new sounds and processes were to be notated. Special aural scores were made (for overview and for the guidance for listeners) which did not require all the details that a musician might need for performance.(13)

A practice not normally seen as "notation", but which nevertheless overlaps with it, is musical analysis. This discipline also deals with the description of music, and has a tradition of employing symbols consisting of letters, numbers and so on as well as schemes, tables and the like. In reality, there is a fluid transition from some of these presentations to aural scores.

In musical analysis it is usual both to systematise observations into historic form categories (such as ABA, reihung, sonata form etc.), to value the individual work and to take up new challenges when asking questions to be answered by the analytical findings. These last two principles are clearly relevant for the use of graphic notation in connection with music therapy, and they even give historical inspiration. The first principle, however, is replaced by psychological interpretations.

For graphic notation, certain analytical models are especially relevant. The principle of division into clearly differentiated sections originated in the tectonic conception of form which influenced much classical music and which saw musical form as a relatively simple, perceivable structure. Another relevant principle is Ernst Kurth's use of the concept of developmental motif. The motif is repeated in an ever varied form and thus carries development. This principle was employed by Beethoven and later composers(14). Here, the music is viewed as a complex organism in a process. Dynamic developments can often be viewed as taking varied repetition as their basis, and an obvious notational parallel in graphic notation is a symbol which is easy to repeat but which can also be varied.

Parameter analysis

Much traditional music teaching and theory, for instance the reading of notes, solfège, harmony, or cipher notation of chords etc. is not directly relevant for the description of complex improvised music. The sound aspect of music demands a broader means of description.

This is the aim of my parameter analysis which sums up and further develops views which have historically been cultivated around new music. These views were inspired by considering the acoustic properties of the sound phenomenon. The sound is considered within a number of dimensions, such as:

- pitch

- duration

- dynamics

- timbre: hard---soft or dark---light or tone---noise

(these three apply to the single sound as well as to the analysis of the process)

- pulse---no pulse (or: regularity of pulse)

- tempo (provided there is a discernible pulse)

- density (how many sounds at once in a given span of time)

- degree of contrast

- musical material in pure cultivation (or "neutral" material)-- quotations

The concept of parameter comes from mathematics and means "dimension for measurement". It seems to be synonymous with "variable" (as used by John Cage). In its original, exact meaning, as employed by composers speaking about serial music in the fifties, a parameter is one single dimension which can be varied continuously. For instance, the human voice can represent a section of pitches by singing a tone sliding evenly from deep to high. This is a continuous variation of pitch - by contrast, the piano divides the continuum into quanta (in a so-called scale!). A more compound notion like "intensity", which could mean that the tone gets both higher and louder and maybe also changes its timbre, cannot be considered a parameter in this sense.

Throughout music history, more and more parameters have been used. Gregorian chant used very few pitches: changes in loudness were first introduced in a stepwise manner in baroque music, with crescendi and diminuendi coming only later. In the romantic period composers created more and more new timbres by means of orchestral combinations of instruments. In this period also, tempo began to be variable. Examples of composition with density and degree of contrast explicitly playing a role in the construction of compositions can be found in new music.

The first three parameters in the list are the easiest to define exactly - they can be measured in Hz (vibrations per second), seconds and decibels. Subsequent parameters become more compound, and additional, individual definitions become required. One specific timbre can be described exactly within a spectrum, but continuous changes are complicated to define, even if one is able to establish principles for directions of change, as I have done here. The contrast between material in "pure cultivation" and that which is "neutral" only makes sense in the context of a certain consensus on what is what, but in practice, the difference between "sound" and "fragments of well-known music" is fairly clear.

When the specific parameters are viewed as being in principle independent of one another, the musical sound can also be viewed as infinitely differentiated - and perhaps also filled with infinitely differentiated forms of meaning! This infinity perspective provides a means of avoiding cliches.(15)

The notion of parameter has become so widespread that it has almost begun to lose its meaning. It is generally used about music and other matters, but often without its exact meaning. This situation is similar to that of a word like "factor" which is also used metaphorically. However, its extensive use in connection with music seems to testify to a general consciousness of the variety of musical material which probably came into being through the use of the word in experimental music.

The view of parameter analysis is a holistic one. The music is seen from upside down - tendencies come before details. It is well suited to complex music in which timbral processes play an important part, as is often the case with improvised music. It might be less well-suited for the analysis of traditional music - it seems that intervallic and harmonic phenomena cannot be described, and I think it would be too artificial to construct "harmonic parameters" to accommodate this. It is difficult to arrange chords into a continuum, and they are better described using more traditional methods.

Bruscia and parameter concepts

Kenneth E. Bruscia's "Improvisation Assessment Profiles" contain a collection of schemes for the description and evaluation of a number of musical characteristics. Included are the parameter concepts "volume", "timbre" and "texture". The latter plays an important role and is considered in sub-divisions. More traditional concepts like rhythm, melody, tonality and harmony also appear.

Bruscia's source for the musical concepts is general language usage. He does not refer to the avant-garde background of music history in which some of the same concepts have an aura of that which is advanced - on the contrary he states that he was dissatisfied with traditional musical analysis which focused on tonal and harmonic structures. He then saw rhythm, volume and timbre as being more general and basic(16). As we can see here, it is possible to arrive at similar results from different roads!

In Bruscia's texts, parameter concepts are coupled with interpretations of what is in balance and what is extreme. For instance, "Texture variability: Register" deals with "the range, amount, frequency and abruptness of changes that are made in the pitch ranges of each voice or part". This is described according to a scale ranging from "Rigid" ("an extremely limited pitch range is used exclusively") to "Random", the description of which runs along these lines: "A pitch range is not established within or between thematic sections because of extreme, abrupt, random changes. No efforts are made to control registers".

Bruscia thinks that music therapists act from such interpretations whether they know it or not. His interpretations are, however, not meant as general recipes. They should be seen as a statement to be reflected on by the individual therapist who may or may not agree.(17)

This misunderstanding is, however, easy to arrive at, not least because of the systematic and graphic arrangement of the text, which resembles that of a standardised psychological test. Thus, in the Norwegian edition, the working schemes leave blank spaces for client, therapist, date etc. as well as for a large number of areas to be graded numerically with reference to Bruscia's personal interpretations.

It would be useful to have a vocabulary of descriptive concepts for common use among music therapists, concepts one could employ relatively independently of the actual interpretation. One could for instance deal with little or much variation in registers and leave an empty space for the therapist's own interpretation of its meaning. Concepts like "rigid", "controlled/uncontrolled" etc. etc. could be put into a similar, but independently placed, psychological vocabulary. One could make clear that the coupling of psychological and musical-descriptive concepts takes place as the individual user's responsibility.(18)

And of course, even though concepts can be shared, we have different priorities - to point out which are the most important is also a personal choice. As I see it, a list of parameter concepts cannot be finite either, not even when considering parameters in the strict sense.

THE NECESSITY OF MUSIC RELATED CONSIDERATIONS WITHIN MUSIC THERAPY

As an introduction, here is a description and some thoughts from practice:

|

Sanne is a 26-year-old blind and girl with Down's syndrome attending music therapy with me. She is hesitating to accept physical contact, she can communicate using a few simple gestures but has no verbal language. She does well motorically - she can move around with a stick and handle doors and stairs. But she uses her voice in a relatively stereotyped manner which I interpret as "quarrelling", protesting in the manner of a little child and at the same time being a sign of withdrawal. However, a quite different mutual communication and a different exchange of emotional expressions has developed in our music-making. My playing on the drum in short statements alternates with clear reactions and sound from her. - One day, Sanne is sitting at the beginning of the music and looks concentrated and expectant. I draw out the time a little and play a beat on the drum. Sanne laughs and looks exceedingly satisfied and amused. I react with my voice - pause - the dialogue continues with pauses and many little variations. How can one beat on a drum bring about such joy and contentment?? A probably very natural explanation for music therapists would point to relationships between people as the central issue, the sounds being locating points of which the meaning has been established through a long process of experience. Sanne knows the drum from having played it herself. She experiences music as less frightening than being touched and as something which satisfies a demand for close contact. This may loosen up a defence which may exist inside her personality and replace it with confidence in the situation which brings about the possibility of having a stimulating, playful exchange of statements, which again brings joy and pleasure and positive expectations. Such a psychological explanation is not wrong, but perhaps there is more to say. Is it not possible that the sound is interesting in itself? That our senses and perception are capable of contemplating it, of being filled with its impression, of being occupied with it, of listening to it in an open way? That Sanne is also listening because the sound has properties which are sufficiently engaging? If this is the case, the individual quality and structure of the sound is extremely important - and thus an aesthetic dimension is also in play. The moment before, I noticed the sound that touched the inner part of my ear in a pleasant way and which then made me listen out into the room where we are sitting. Already in retrospect, I now contemplate the delicate transition between its crisp attack and the swelling, slowly vibrating, deep sound which came out, spread out and has now disappeared. And I listen on and would like more things to happen... |

Psychodynamic music therapy takes as its basis psychological theories. For instance Freud, Jung, Grof, Mahler, Stern, Kohut and Winnicott are frequently cited writers in a music therapy context, and they have long since been recognised within the domain of general psychology. Music therapists can refer to such theories as a background for their own methods or they can let the connection be implicitly implied. Authors advocating "qualitative research" have since the beginning of the nineties identified as an ideal a rethinking of music therapy research methodology.(19)

But this last development has stemmed from general trends in the theory of science and psychology. Musicology has not yet seriously entered the scene, despite its obvious relevance. With its overview of philosophical views of musical aesthetics, with its wide range of methods for describing music and with its observations of the shifting cultural and historical forms of music, it offers tremendous possibilities both for grounding the psychological understanding of music and for giving it a broader perspective.

Any good psychodynamic therapy method demands the giving of one's full and complete attention to the client and his/her music and the moderation while listening of one's own judgements and reflections - the "noise" inside the therapist which blurs the perception of what is going on in the outer world - so as to secure contact with the client's music. This attention on the therapist's part should have a methodical grounding. Here, descriptive concepts are important - a fact which deserves more attention in music therapy literature. Descriptive terminology permits critical reflection on psychological interpretations and serves to minimise the subjective bias - see above under "Graphic Notation - exercise with 3 columns".

Music therapy is part of a larger cultural and historical context. Our experiences of creativity within generally accessible music can inspire others - cf. Ruud (1990) (20) - and become part of a larger discussion. Niedecken (1986) also shares this line of thought and stresses the perspective of music therapy as inspiration for a critical view of music culture. Aesthetics is also an area with immediate significance for clients of music therapy, cf. Stige (1998).(21)

That which is psychological takes place within the limits set by the medium of music, and conversely, the medium of music is to a great extent what we make it. Metaphorically, music can be seen as a means of transport - for instance, a horse or an aeroplane - and the journey and its medium cannot be totally separated. If the horse or the aeroplane is kept in perfect condition, it will yield better journeys and inspire us to make more of them! (22) And here is one more metaphor about the same thing: inside the music therapist there is a musician. While the therapist has a compass showing the general direction, without which the process might go round in circles, the musician has a knowledge of the local context which can take them through the territory, even if it is difficult to access.

Set against the background of the therapy being a process which is probably in many cases an extended one demanding patient work from the therapist, the immediate aesthetic unity and coherence in the listening and practising of music can be stimulating for the therapist. The music can be sensual, dynamic, filled with atmosphere, communicating (etc.) to such a degree that it has consequences for the understanding of how much music has to offer - and music history can be a guide to wild experiences and thought-provoking studies.(23)

Motivations and goals for the human being in therapy can be described psychologically. The road which is followed and the learning process leading to development towards these goals can be viewed both with the aid of concrete description of the music and with the aid of aesthetics. The music-related theoretical backgrounds dealt with here are tools which can support the music therapist's practical activity and put it into perspective.

LANGUAGE THEORY AS A LINK BETWEEN PSYCHOLOGICAL AND MUSICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Language theory and semiology or semiotics, the science of sign systems, has long accepted the fact that language has both very individual and very structured properties. Here, a classical communication model will be explained. (24) As I see it, this is an encouraging example showing how complex interdisciplinary relations can be summed up in one model. "Language must be studied taking into account all its multitude of functions", Roman Jakobson states in his article "Linguistics and poetics" from 1960 (25), and he set up the following, now classical, model:

|

CONTEXT (Referential function) SENDER------------- MESSAGE--------------RECEIVER (Emotive function) (Poetic function) (Conative function) CONTACT (Phatic function) CODE (Metalingual function) |

The model illustrates the fact that language has several functions. It can express emotions, give informative statements about the outer world, appeal to the receiver (emotive, referential and conative functions). The phatic function seeks out and confirms the contact - "Hello, are you there?". And the metalingual function subjects the language itself to discussion, as when for instance one is asking about the meaning of a particular expression. The poetic function "focuses on the message in itself".

Eco calls the poetic function "self-mirroring". When it prevails, the nature and structure of the message itself is focused upon - concrete statements and expressions of emotions are for instance less important. It lends itself easily to projections. (26)

When the aesthetic function prevails within a communication process, we consequently do NOT have a simple sending back and forth of signals, as in figure 7:

|

SENDER ---- (message) -------> RECEIVER |

Figure 7 - emotive and referential functions.

Rather, there is a shared, in-the-moment working on the "message" - the music is not just a means, but a medium in which both parts can alternatingly identify with a common object. The common object is being creatively worked upon - see figure 8. (27)

|

MUSICIAN I <-------> (message) <--------> MUSICIAN II |

Figure 8 - poetic function.

Drawing a parallel with the therapeutic meaning of the practice of improvised music, we can claim, for instance, that expressing one's emotions and feelings is only one function among others. The function which communicates emotions depends on the aesthetic one. This means that definite psychological themes are so to speak "blacked out" to a certain extent when aesthetic work dominates. (28)

Playing, experimenting, exploration, meeting the unknown, a certain amount of fertile chaos, boldness - all these are relevant ingredients for therapeutic endeavour leading to the integration of new things into the personality, an endeavour which certainly takes place to a significant extent within the practice of music-making itself. When unconscious matters are explored, this activity is by its very nature a meeting with the unknown which only gradually becomes more identifiable. The concept of the transitional object contains this aspect of indeterminacy while at the same time referring to the psychological context. It thus unites aesthetic and psychological characteristics, and might be a starting-point for further interdisciplinary reflections.

Stockhausen characterised the experience of meeting the unknown in this striking way: "New music is, in fact, not so much the result, not so much the sound resulting from thinking and feeling with modern composers (admittedly, it is that, too), but rather a music which even for those who invent it, who allow it to come into being, is strange, new, unknown. Only after having heard it, such a new music (which one rather finds than invents) causes new thinking and feeling". (29)

With inspiration from Jakobson it is possible to perceive therapy music as a language with several functions in which aesthetic, explorative activity takes place, in which the participants send more specific personal messages to each other and in which extended developments over time can be perceived.

Aigen, Kenneth (1991): The Roots of Music Therapy: Towards an indigenous research paradigm. Manuscript (Dissertation).

Bailey, Derek (1992): Improvisation. Its Nature and practice in Music. Dorchester (The Brit. Libr. Nat. Sound Arch.).

Good information about improvisation in many different forms of music. Excellent discussions of the nature of improvisation, also in free improvisation. Good documentation of interviews with many different musicians. Editions also exist in Flemish, German, French, Italian and Japanese.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1976): Improvisation i kompositionsmusikken efter 2. verdenskrig. Manuscript (paper from M.A. study).

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1979): Undersøgelser omkring eksperimentbegrebet og eksperimentets rolle i vestlig kunstmusik efter 1945 (M.A. thesis, University of Copenhagen).

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1981): "Ny musik som eksperiment og alternativ", Dansk Musiktidsskrift 6.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1984): "En videnskabsteoretisk model af musikkens rolle i musikterapi", manuscipt.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1986): To musikalske eventyrere. Cage og Stockhausen. Århus (PubliMus).

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1988): "Om mine tolkninger af de kliniske improvisationer " and "en diskussion af undersøgelsesresultaterne"..." in Lund, Grethe: Skizofreni og musik. Aalborg (Aalborg Universitetsforlag).

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1988/89): "Intuitiv musik og grafisk notation som universitetsdiscipliner. Om nogle færdighedsfag ved Musikterapistudiet på Aalborg Universitetscenter". Dansk Musiktidsskrift 6.

Freely improvised music and graphic notation (aural scores) as teaching subjects on the music therapy training course in Aalborg, Denmark, are described. Examples from students' work, scores to improvise from as well as listening scores, are quoted. Historical and philosophical perspectives are discussed.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1990ffA): Intuitiv Musik - en Mini-håndbog. Målgruppe "unge og voksne". Photo-copied.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1990ffB): Intuitive Music - a Mini-Handbook. Photo-copied.

Handbook for people who wish to play or teach freely improvised music and improvisation pieces. With sections on how to start with different types of groups, training of musical awareness, parameters of the musical sound, the history of improvised music and a bibliography.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1991): "Intuitiv musik på Aalborg Universitetscenter". Levande Musikk. Nordisk Musikkterapikonferanse 1991. Sandane (Høgskulutdanninga på Sandane).

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1992ffA): Graphic Notation. Systematic Exercises for making listening scores. Photo-copied.

Textbook to be used along with training in the practice of graphic notation. Describes method; exercises; bibliography; collection of examples.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1992ffB): Grafisk notation. Om metodiske øvelser i at lave lyttepartiturer. Manuscript.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1993 (publ. 1995)): "Graphic Notation as a Tool in Describing and Analysing Music Therapy Improvisations", Music Therapy. The Journal of the American Association for Music Therapy, vol. 12, no. 1.

Presents graphic notation as the making of listening scores to memorise or analyse improvised music therapy processes, capturing also those aspects the usual music notation would not cover. An example in some detail is shown, the music taken from a well known Nordoff/Robbins recording. A training method, involving graphic brainstorms, using coordinative systems and other frameworks, an interpretative method including working on specifically musical counter-transference and special graphic exercises are outlined. Work by students at Aalborg University, Denmark, is quoted. General perspectives including relations to music analysis in musicology and to the history, epistemology and cultural status of musical notation is discussed.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1994/95): "Improvisation - nu og før", Dansk Musiktidsskrift 6.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1995): "Ny musik og improvisation", Musica Nova forår 95, programbog. København.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl (1996): "Wie die komponisten ihre Musik liebten. Klangsensualismus als wesentliches Merkmal des frühen Serialismus", MusikTexte 62/63.

Bergstrøm-Nielsen, Carl and others (1982/83): "Stockhausen privat", Dansk Musiktidsskrift 4.

Brindle, Reginald Smith (1975 - 2nd ed. 1986): The New Music: The Avant-garde since 1945. Oxford (OUP).

Important music history book that also deals with intermediate forms of music between composition and improvisation (however, not free improvisation and improvisation groups). Many notational examples. Page numbers in old and new edition match each other.

Bruscia, Kenneth E. (1987): Improvisational Models of Music Therapy. Springfield, Ill. (Charles E. Thomas).

Bruscia, Kenneth E. (1994): IAP - Improvisation Assessment Profiles. Kartlegging gjennom musikkterapeutisk improvisasjon. Oversettelse, introduksjon og kommentarer av Brynjulf Stige og Bente Østergaard. Sandane (Høgskulutdanninga på Sandane, N-6860 Sandane, Norge).

Norwegian re-edition of the author's analytical profiles first presented in the book Improvisational Models of Music Therapy. The author's preface, however, is in English and contains some important later comments.

Cage, John (1971, 73): "Experimental Music: Doctrine", Silence (s.13-17). London (Calder and Bryars).

Central text about experimental music.

Childs, Barney (1974): "Indeterminacy", artcle in Vinton (ed.): Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Music (N.Y. 1971). London.

Concise and important text about a major direction of experimental music.

Dammeyer Fønsbo, Charlotte (1998): På tværs af grænser - et speciale om musikterapeutisk behandling af traumatiserede flygtningebørn. Final paper. Manuscript, Aalborg University, Music Therapy.

Employs graphic notation within a case-story.

Eco, Umberto (1971): Den frånvarande strukturen. Introduktion till den semiotiska forskningen. Lund (Bo Cavefors).

Eco, Umberto (1989): The Open Work transl. by Anna Cancogn. With an introduction by David Robey. London (Hutchinson Randing).

Flusser, Elisabeth (1983): Approche du Jeu Musical. Mémoire pour le diplome de musicien-animateur, Chalon/Saone.

Gieseler, Walter (1975): Komposition im 20. Jahrhundert. Details - Zusammenhänge. Ed. Moeck, Nr. 4015.

Book with an abundance of interesting notation examples, some of which also in colour. As a music history book, however, problematic because the important American part of the development is not viewed in relation to its own background. Extensive sections with indexes and bibliographical information related to the many examples.

Guiraud, Pierre (1971): La Sémiologie. Paris (Presses Universitaires de France). Part of the series: "Que Sais-Je?". Le point des connaissances actuelles.

Elaborates on the model of Jakobson and gives a broad semiological perspective.

Guiraud, Pierre (1975): Semiology ... Translated by George Gross. London (Routledge and Kegan Paul).

See Guiraud (1971).

Jakobson, Roman (1974): "Lingvistik och poetik" (1960) i: Poetik och lingvistik. Litteraturvid. bidgar valda av Kurt Aspelin och Bengt A. Lundberg. Stockholm (Kontrakurs).

Jensen, Bent (1998): Om at finde vej til et hul i muren. Terapeutisk progression i musikterapi med skizofrene, belyst ud fra patient-terapeut-relationen, analyse af den musikalske interaktion og fortolkning af modoverføring. Speciale i musikterapi. Manuscript, Aalborg University.

Employs graphic notation within a case-story.

Jørgensen, Anne Møller (1986): Den terapeutiske relation - set fra terapeutens side. Final paper. Aalborg University.

Klahn, Anne (1985): Fra kliché til symbol - tegning og psykoanalytisk praksis. Paper written during the study of clinical psychology, University of Copenhagen.

Langenbach, Michael (1998): "Zur körpernahen Qualität von Musik und Musiktherapie und der Angemessenheit ihrer graphischen Notation", Musiktherapeutische Umschau 19, p.17-29.

From the English summary by the author: "The corporeal quality of music provides an important way of expressing presymbolic and preverbal ways of experience... It is argued that graphic notation of improvisations in music therapy is best suited among other ways of musical notation to catch this corporeal quality of music". The activities of CBN are mentioned.

Lorenzer, Alfred (1972): Zur Begründung einer materialistischen Sozialisationstheorie. Frankfurt (M) (Suhrkamp).

Mahns, Wolfgang (1998): Symbolbildungen in der analytischen Kindermusiktherapie. Eine qualitative Studie über die Bedeutung der musikalischen Improvisation in der Musiktherapie mit Schulkindern. Ph.D.-dissertation. Manuscipt, Aalborg University.

Mathiasen, Stephen (1972): Psykologisk vækst. Copenhagen.

Niedecken, Dietmut (1986): Einsätze. Material und Beziehungsfigur im musikalischen Produzieren. Hamburg (VSA-Verlag).

Nielsen, Poul (1971): Den musikalske formanalyse. Fra A.B. Marx' "Kompositionslehre" til vore dages strukturanalyse. Copenhagen (Borgen).

Pavlicevic, Mercedes(1997): Music Therapy in Context. Music, meaning and Relationship. London (Jessica Kingsley Publ. Ltd.).

Pedersen, Inge Nygaard og Scheiby, Benedikte Barth (1981): Musikterapeut - Musik - Klient. Erfaringsmateriale fra den 2-årige musikterapiuddannelse i Herdecke 1978-80. Med kassettebånd. Especially on musical analysis and graphic notation: p. 89-101 and 155-63. Aalborg Universitetsforlag.

Pedersen, Inge Nygaard og Scheiby, Benedikte Barth (1983): "Vi zoomer os ind på musikterapi - Nej, ikke musik og terapi, men musikterapi", Modspil nr. 21.

Perls, Frederick; Hefferline, Ralph E.; Goodman, Paul (1951): Gestalt Therapy. Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality. New York (Dell Publishing Co. - A Delta Book).